Introduction

I am currently taking an Introduction to Linux course over at the Linux Foundation. Today, I learned about the boot process of Linux and the filesystem structure of Linux machines.

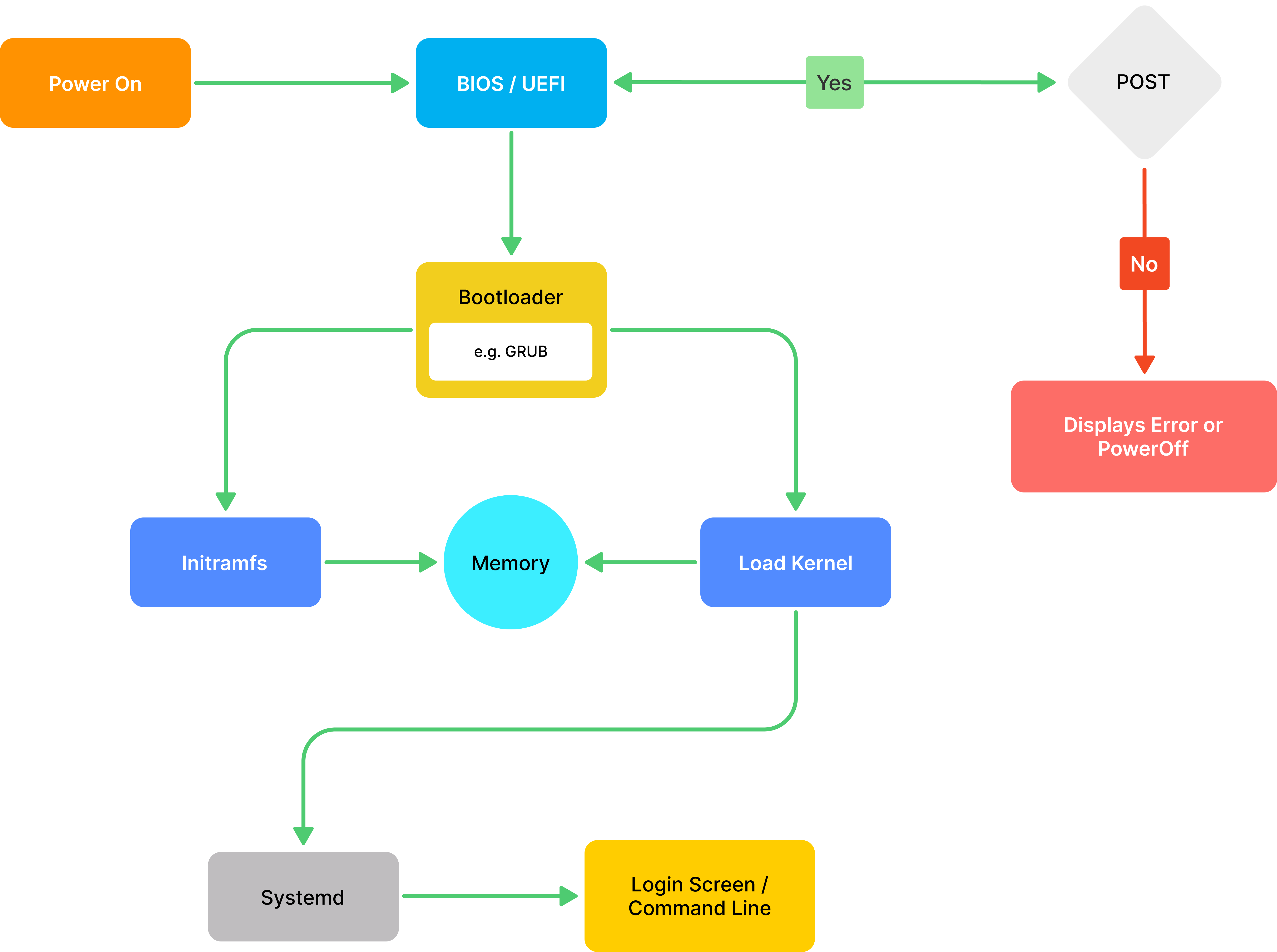

In short, the Linux boot process starts when the computer is powered on. The BIOS initializes the system and then the bootloader is invoked. The bootloader calls the initramfs (a filesystem image containing programs and binary files necessary for mounting the proper root filesystem). This is how Linux starts, and I will go into more detail about it later in the blog.

As for the Linux filesystem, unlike windows, there is no concept of individual drives. Everything is organized under a hierarchy, as described in the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard.

Let’s Talk About the Linux Boot Process

The boot process begins as soon as you press the power button, and from there, it follows a series of steps:

POST (Power-On Self Test)

After pressing the power button, the BIOS starts and runs the POST (Power-On Self Test). This process checks if all the hardware components, such as the RAM, hard drive, network cards, etc., are functioning correctly. If a failure occurs, the system will stop and display an error on the screen, or it might simply turn off.

BIOS (Basic Input/Output System)

Once the POST completes successfully, the BIOS takes over. The BIOS is a firmware that resides on the motherboard and is responsible for initializing and testing hardware components (like the CPU, RAM, and storage devices). It is also in charge of loading the bootloader.

Bootloader

Once the BIOS has handed over control, the bootloader is loaded from the storage device (such as your hard drive or SSD). At this point, the system does not access any mass storage media. The bootloader, such as GRUB (Grand Unified Bootloader), is responsible for loading two key components into memory:

- The Kernel: The core of the operating system, responsible for managing hardware and system resources.

- The Initramfs (Initial RAM Filesystem): A temporary root filesystem loaded into memory. The initramfs contains essential binaries, drivers, and scripts required to mount the real root filesystem. It helps the kernel set up the environment for system startup.

Both the kernel and initramfs are loaded into the system’s RAM (Random Access Memory). Once these components are loaded, the bootloader hands over control to the kernel.

Kernel

The kernel is the heart of the operating system. After the bootloader loads both the kernel and initramfs into RAM, the kernel takes control of the system. It initializes hardware components and prepares the system to run processes.

Once the kernel has successfully initialized the system, it starts the first process, which is typically systemd. Systemd is a system and service manager that initializes and manages system services, processes, and system states during bootup.

Systemd

Once the kernel loads systemd, it becomes the first user-space process with PID 1. Systemd is responsible for:

Initializing System Services: It starts all the necessary system services (e.g., networking, logging, hardware services, etc.) by running a series of unit files that define how each service should start.

Managing Processes: Systemd continues to manage processes and handle system states as the system continues to boot and run.

Mounting Filesystems: It also takes over the mounting of filesystems (other than the root filesystem), ensuring all necessary partitions are available for use.

At this point, the system is up and running, and systemd is in charge of running and managing the system’s services.

Login

After systemd has initialized all necessary services and mounted filesystems, the final step in the boot process is to present the user with a login screen. This is typically a graphical or terminal-based interface where the user can authenticate themselves to access the system.

Graphical Login (Display Manager): In modern Linux distributions with a graphical environment (like GNOME, KDE, etc.), a Display Manager (such as GDM, LightDM, or SDDM) is started by systemd. The Display Manager is responsible for handling user authentication and starting the graphical session. It displays the login screen, where users can enter their credentials (username and password) to log into the system.

Text-based Login: In systems without a graphical environment (or in some server environments), the login screen is a terminal-based prompt. Users are prompted to enter their username and password via a text console (e.g., using getty or agetty). Once authenticated, the user is granted access to the system.

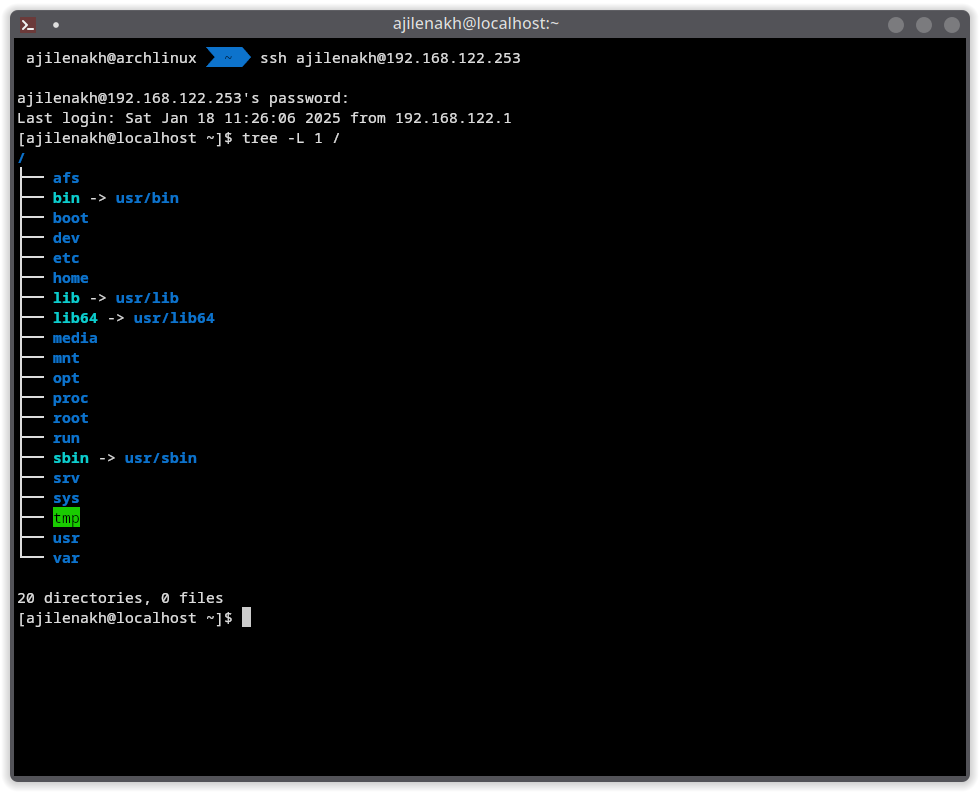

Understanding the Linux Filesystem

Now that we’ve talked about how the Linux boot process works, let’s dive into how the Linux filesystem is organized. Unlike Windows or macOS, Linux doesn’t rely on traditional “drives” (like C:, D:, etc.). Instead, everything is organized into a single, unified directory structure.

Imagine your Linux system as a giant tree, with directories branching out from a central point—the root directory (represented as /). All files and directories in Linux are part of this single tree. This approach is part of what’s called the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS), which is a guide that dictates how Linux filesystems should be structured.

Here’s a basic overview of some important directories you’ll encounter:

- / (Root Directory): This is the base of the filesystem, where everything starts. It contains all other directories, files, and devices.

- /bin: Contains essential system binaries (programs) that are required for system operation.

- /etc: Stores configuration files for system-wide settings and services.

- /home: This is where user directories are stored. Each user has a directory here to store their personal files.

- /var: Contains files that are expected to change frequently, such as log files and application data.

- /usr: This directory holds non-essential user programs and data, like installed software packages.

To give you a better idea of what the root directory looks like in practice, here’s a RHEL root directory image that shows how these directories are laid out on a real system.

As you can see, the Linux filesystem is structured like a tree, with / at the top and various branches leading to different types of files and directories. The /etc directory is a central place for configuration files, while /home is where your personal files are stored.

This structure might seem a bit different from what you’re used to on Windows or macOS, but once you get the hang of it, it’s actually pretty efficient and intuitive.